OSINT Discovery for Credit Unions Case Study

Gateway to Mass Exposure:

How a single GitHub leak exposed 23 credit unions and financial institutions revealing a shared supply chain security risk

At Exploit Strike, we build tools to complement our penetration testing and offensive cybersecurity services. Our most recent creation, Exploit Shield, is an OSINT (Open Source Intelligence) leak detector which helps organizations discover and take down sensitive leaks.

Most Exploit Shield findings involve chasing down a leaked secret in a GitHub repo, misconfigured repositories accidentally set to public, or the occasional client secret for a health record fetching API.

This one was different.

It started the same way most things do: one alert, one config file, tied to a known client.

At first glance, it looked like a small mistake in a public GitHub repository. The kind of hard-coded secret mess cybersecurity teams deal with every day.

While the affected organizations were a mix of banks and credit unions, the underlying exposure was identical across all of them. This was a major leak involving:

23 credit unions

2 large payment processors

1 single vendor in the software supply chain leaking all the goods.

This was a visibility failure that traditional penetration testing did not detect and quietly affected financial institutions serving millions of people.

The OSINT Discovery

We were monitoring GitHub for secrets associated with one of our credit union clients. Exploit Shield flagged a .properties file that appeared to contain core banking credentials. The file was hosted in a public GitHub repository, outside any monitored internal environment.

The filename matched the credit union’s established naming convention, which would ordinarily warrant attention. However, an anomaly was discovered that did not align with the standard pattern.

There wasn’t just one file for one credit union.

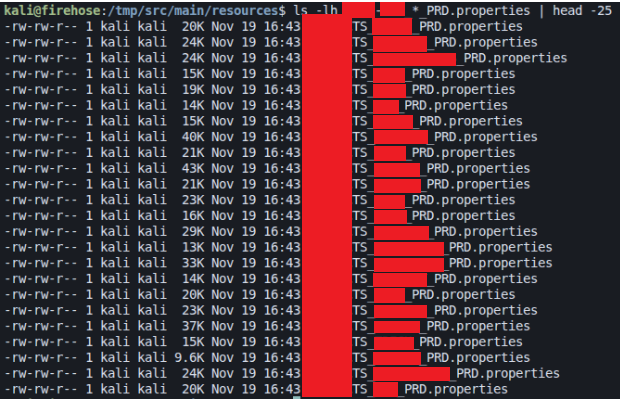

In the same directory, there were 23 nearly identical configuration files, each named for a different financial institution.

That immediately raised the stakes.

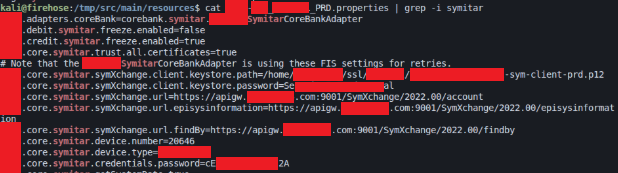

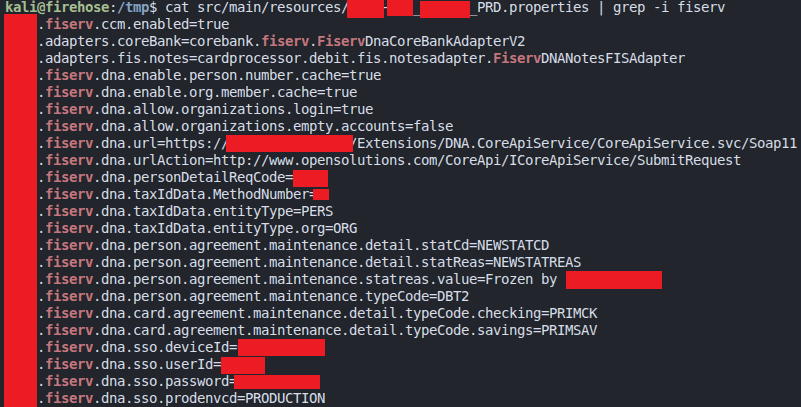

The contents of the files weren’t placeholders. They included hard-coded credentials tied to core banking systems like Symitar and Fiserv DNA, along with API keys used to connect to Visa and MasterCard payment processors.

Symitar core banking URLs and credentials

Fiserv DNA core banking URLs and credentials

At that moment, this stopped being a client issue.

Seeing the Pattern: Expanding the Blast Radius

Any good pentester can recognize patterns in source code. From a risk perspective, this was a software supply chain exposure, not an isolated coding mistake.

Each credit union had its own configuration file following the same structure. The only differences were the organization name, the core banking platform, and the credentials themselves. Institutions running Symitar had Symitar URLs and credentials, while those on Fiserv DNA had equivalent configurations.

That’s when it became clear we weren’t simply looking at a third-party supply chain leak for our client. We were looking at a shared application, owned by a third-party vendor, used as an integration layer between the retail banks and Visa/MasterCard.

And its source code, containing hard-coded secrets, became publicly accessible.

The Role of the Intermediary: A Risk Concentrator

This intermediary functioned as a risk concentrator.

Most financial institutions don’t directly integrate their core banking platforms with payment networks. They rely on specialized processors and integration providers to do that work.

In this case, the intermediary acted as a shared integration provider and gateway processor used by financial institutions.

From a third-party cybersecurity risk perspective, that makes the intermediary part of every downstream organization’s attack surface.

Third-Party vendor questionnaires rarely ask:

Where source code is stored,

Whether production secrets are hard-coded, or

Whether public repositories are actively monitored.

This is exactly the scenario modern supply-chain risk frameworks are trying to address.

No One Noticed

This repository had been public and secrets published from May 2022 to February 2025.

During that time:

None of the 23 credit unions or financial institutions detected it

Visa and MasterCard did not detect it

Bug bounty programs didn’t report it

The third-party vendor itself was unaware

Vulnerability Disclosure and Legal Considerations

Once we understood the scope, we stopped and asked a hard question:

“How do we disclose this with each affected organization without causing harm given the sensitivity and breadth of impact?”

The legal guidance was clear: information that is publicly accessible should be disclosed responsibly, provided the intent is remediation and not reputational damage.

We focused on scope, impact, and urgency, and attempted to contact each organization involved.

Reaching the Third-Party Vendor the Hard Way

Getting in touch with the leaking organization took persistence, as is with most responsible disclosures.

Emails went unanswered. Support channels were silent. Contact forms led nowhere.

Usually, if I try to contact an organization about a leak via written correspondence, they write me off as spam.

Eventually, we called the sales line. Just to reach a human.

That call connected us to the CTO, who also served as head of cybersecurity. When shown the repository, the reaction was immediate.

“Holy s***, That’s all of our code. That’s not supposed to be public.”

Within an hour, the repository was taken down. The contractor responsible was contacted and remediation began.

The Hardest Part Was Reaching the Right People

Once we understood the scope of the exposure and the vendor removed the leak from GitHub, the technical work was largely done.

What remained was disclosing the impact to the victim organizations.

The scale was intimidating. Twenty-three banking entities were affected by the same third-party leak, and none of them were aware it existed.

There was no shared disclosure channel. No centralized notification. No indication that the vendor had identified or escalated the issue.

We started with the obvious paths and looked for published vulnerability disclosure programs. We checked for security.txt files. We searched for security and abuse email addresses. When those were missing, we used general contact forms, help desks, and front desk phone numbers.

In many cases, no one responded.

Without a defined intake path, legitimate disclosures are filtered out and treated the same as spam or social engineering attempts. Not to mention every cybersecurity professional has sales fatigue, so no one can blame them for writing me off as a sleazy salesman.

In several cases, we only reached security teams after repeated attempts and escalation through unrelated departments.

When we did reach the right people, the response was consistent.

They understood the severity, validated the findings, and acted.

The delay happened before that point.

That delay matters. Exposed credentials do not wait for internal routing. While messages sit unanswered, secrets remain accessible, searchable, and reusable.

In a shared vendor scenario, the impact compounds. One exposure affects dozens of institutions at the same time, each unaware of the others. This is one of the least visible risks in responsible disclosure today. Many organizations assume that if something serious were exposed, someone would notify them through the right channel.

This incident shows how fragile that assumption is.

Why Penetration Testing Missed This

Exploit Shield did not start as a commercial product.

It was built to support penetration testing.

We developed it to answer a recurring question during engagements:

“What sensitive material tied to this organization is already public, but not visible from inside the network?”

That capability was originally used as part of OSINT reconnaissance during penetration tests. A single scan. A snapshot in time. No continuous monitoring.

That distinction matters.

All 23 affected credit unions underwent regular penetration testing. In some cases annually. In others more frequently. Across all of those engagements, this exposure went undetected. Code leaks generally live outside traditional pentest scope. The leaked material did not exist on the organization’s infrastructure. It lived in a third-party repository, owned by a vendor, maintained by a contractor, and publicly accessible.

In this case, detection came from continuous brand-based reconnaissance performed for a client, Exploit Shield. That is how the exposure surfaced. Not through internal alerts. Not through vendor notification. Not through scheduled assessments.

This incident reinforces a simple lesson.

Public exposure reconnaissance is not a replacement for penetration testing. It is a necessary complement. Without it, organizations can complete regular assessments and still miss risks that exist entirely in public view.

What “Good” Would Have Looked Like

In hindsight, this exposure was preventable.

A few controls could have changed the outcome entirely. None of these are exotic; they’re just uncommon:

Penetration Test scope that included mapping the organization’s OSINT footprint

Continuous public attack surface monitoring across the public web

Continuous monitoring of each vendor’s footprint on the public web

Third-Party Vendor requirements around source control hygiene

Clear policies forbidding hard-coded production secrets (on the part of the vendor)

Lessons Learned

1. Third-Party Code Is Part of Your Attack Surface

If a vendor’s application connects to your production systems, its source control hygiene matters as much as your own.

2. Penetration Testing Scope Does Not Equal Exposure Scope

Penetration tests evaluate authorized systems at a moment in time. Public exposure often exists outside those boundaries and can persist for years unnoticed.

3. Public Does Not Mean Low Risk

Public repositories frequently contain production-grade secrets. Accessibility does not reduce impact.

4. Visibility Is the Real Vulnerability

This failure was not technical sophistication. It was a lack of awareness of where sensitive artifacts existed.

5. Disclosure Is a Human Process

Without a clear intake path, legitimate disclosures are filtered out alongside spam and social engineering attempts.

A Note on the Research Behind This

This type of incident is very common.

Over the past six months, we’ve been running a focused research effort alongside our penetration testing work to understand how often sensitive internal information leaks into public developer platforms, and why it stays there.

In one penetration test, we uncovered a repository created by a former employee who had left the organization months earlier. Before leaving, they had stashed internal notes in a personal repository. Those notes included domain administrator credentials, service account passwords, and data center backup credentials.

That pattern has repeated itself more times than we expected. The sources are rarely surprising. Most of the leaks we encounter come from places teams use every day: GitHub, Postman, Bitbucket.

As part of this research, we’ve worked with organizations across multiple industries, including major big-box retailers, global automotive manufacturers, credit unions, banks, healthcare providers, and health insurance companies. In each case, the work involved identifying exposed credentials or sensitive artifacts in public platforms and coordinating responsible disclosure and remediation.

What is surprising is how unresponsive most organizations are to responsible disclosure and how long these artifacts persist without action.

Across roughly six months of research, we’ve identified and helped remove dozens of repositories containing sensitive material. In the process, we’ve discovered hundreds of exposed credentials, ranging from individual service accounts to high-impact access like domain administration and client secrets.

In nearly every case, the leaks weren’t the result of malicious intent. They were the result of individuals using personal resources to escape the restrictive corporate environment, stashing notes while preparing to leave an organization, or simply setting a sensitive GitHub repository public.

The leaks don’t always come from a corporate account. More often than not, commit authors have Gmail email addresses. These cases are especially difficult to track, as they fall outside most corporate monitoring tools. They are the unknown-unknowns.

That context is important, because it reinforces the core lesson of this article: most of the risk doesn’t come from attackers doing something clever. It comes from organizations not realizing what people with internal access are purposefully or accidentally exfiltrating.

Closing Thoughts

This wasn’t a breach, there was no attacker, no exploit chain, no ransom note. But it represents a real cybersecurity exposure that existed entirely in public view and carries an extreme level of risk if undetected.

Every regulated organization should implement three non-negotiables:

Continuous OSINT monitoring tied to brand, vendors, and developers

A public disclosure intake (security.txt or VDP) that reaches security staff

Penetration testing scope that explicitly includes OSINT discovery

Without these, banks and credit unions will continue to pass audits and complete penetration tests, but still carry leaked baggage in plain sight.

For issues involving exposed credentials or direct access to regulated financial institutions, Exploit Strike will notify all impacted parties after 30–60 days if remediation status is unclear or unconfirmed by third party vendors.